The Church of the Fathers

The establishment of the Capuchin Mission in Deir ez-Zor dates back to the early 20th century, with the Latin Catholic Church known as the Capuchin being one of the oldest

The establishment of the Capuchin Mission in Deir ez-Zor dates back to the early 20th century, with the Latin Catholic Church known as the Capuchin being one of the oldest

A secondary school in the city of Deir ez-Zor, built in 1910, and considered one of the oldest schools in the eastern region of Syria. The Euphrates Secondary School is

Mari (Tell Hariri) is an archaeological site of exceptional significance, located approximately 11 kilometers northwest of Al-Bukamal on the right (western) bank of the Euphrates River, and about 115 kilometers

Rising majestically on the banks of the Euphrates River near the city of Al-Mayadin in eastern Syria, Qal’at al-Rahba (The Citadel of Rahba) stands as a monumental reminder of the

Dura-Europos—modern-day Al-Salihiyah—is an important archaeological site located in the Syrian Desert near Deir ez-Zor. The city is home to the world’s oldest known house church, as well as some of

Dur-Katlimmu is a prominent archaeological site in Syria’s Deir ez-Zor Governorate, identified as the ancient Assyrian city, now known as Tell Sheikh Hamad, approximately 70 kilometers east of Deir ez-Zor

Tekkiyeh of Sheikh Wais—also known as the Great Naqshbandi Tekkiyeh—is a small mosque (zāwiya) situated in the heart of Deir ez-Zor, Syria. The term tekkiyeh is the Turkish equivalent of

Tekkiyeh of Sheikh Abdullah—known as the Small Naqshbandi Tekkiyeh—is a modest mosque (zāwiya) located in central Deir ez-Zor, Syria. The term tekkiyeh, a Turkish analogue to khanqah or zāwiya, has

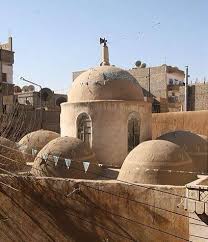

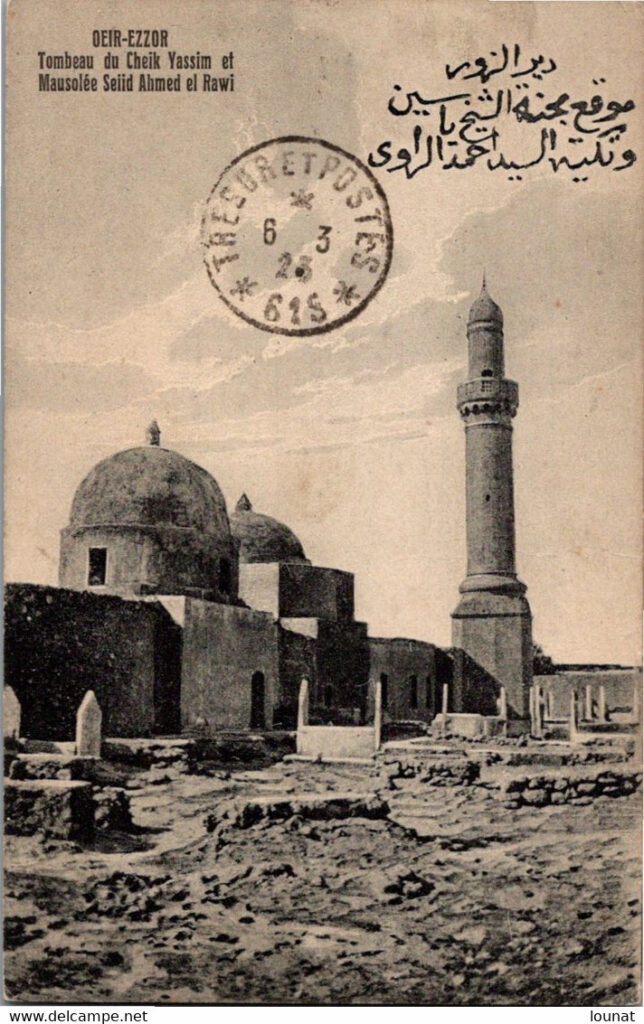

Tekkiyeh al-Rāwī is a modest mosque (zāwiya) located in the heart of Deir ez-Zor, Syria, within the Sheikh Yassin district. The term tekkiyeh, borrowed from Turkish and analogous to a

The Old Covered Markets of Deir ez-Zor, locally known as al-Souq al-Maqbi, are a collection of historic commercial marketplaces established in 1865, during the final years of Ottoman rule. They

جميع الحقوق محفوظة لصالح JCI Aleppo

All rights reversed to JCI Aleppo